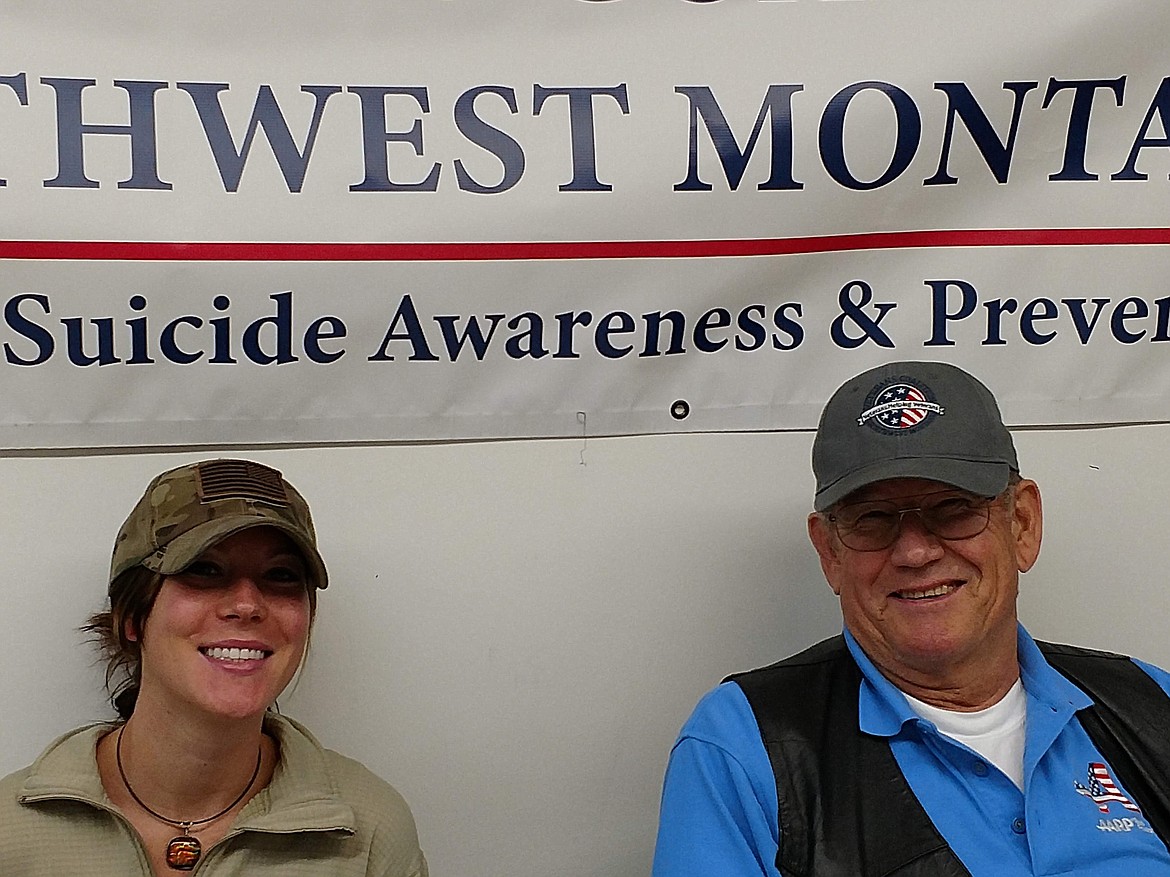

Veterans serve on the front lines of suicide prevention

Rick Morrow knew time was limited when he got the call.

A distraught woman had told his pastor that her husband, an Army veteran, was suffering a severe mental health crisis...

Become a Subscriber!

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login