Former clients were unaware Hartman lacked a Montana license

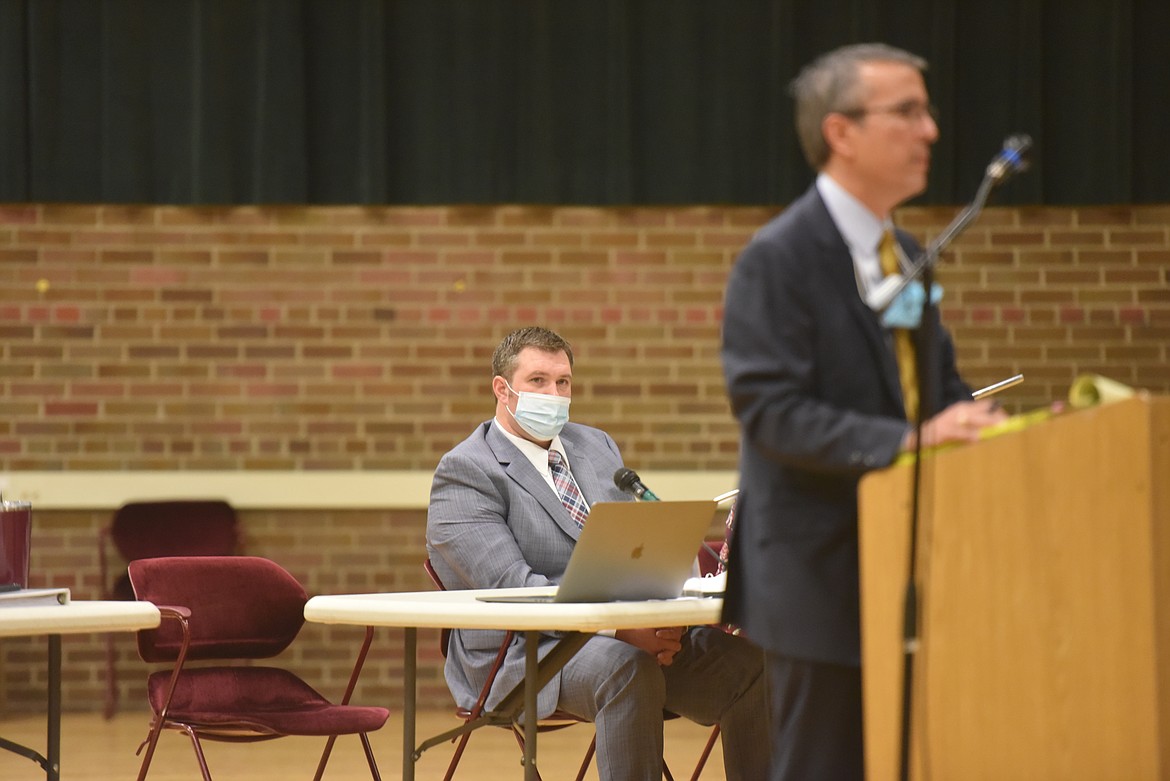

During the opening week of the trial of a Bonners Ferry man accused of financial crimes, prosecutors called on witnesses ranging from allegedly exploited elderly clients to investigators from the state auditor’s office.

Kip Hartman, 35, faces nine felonies in Montana stemming from the sale of annuities to Libby and Troy residents...

Become a Subscriber!

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login