Health board meets as coronavirus cases jump

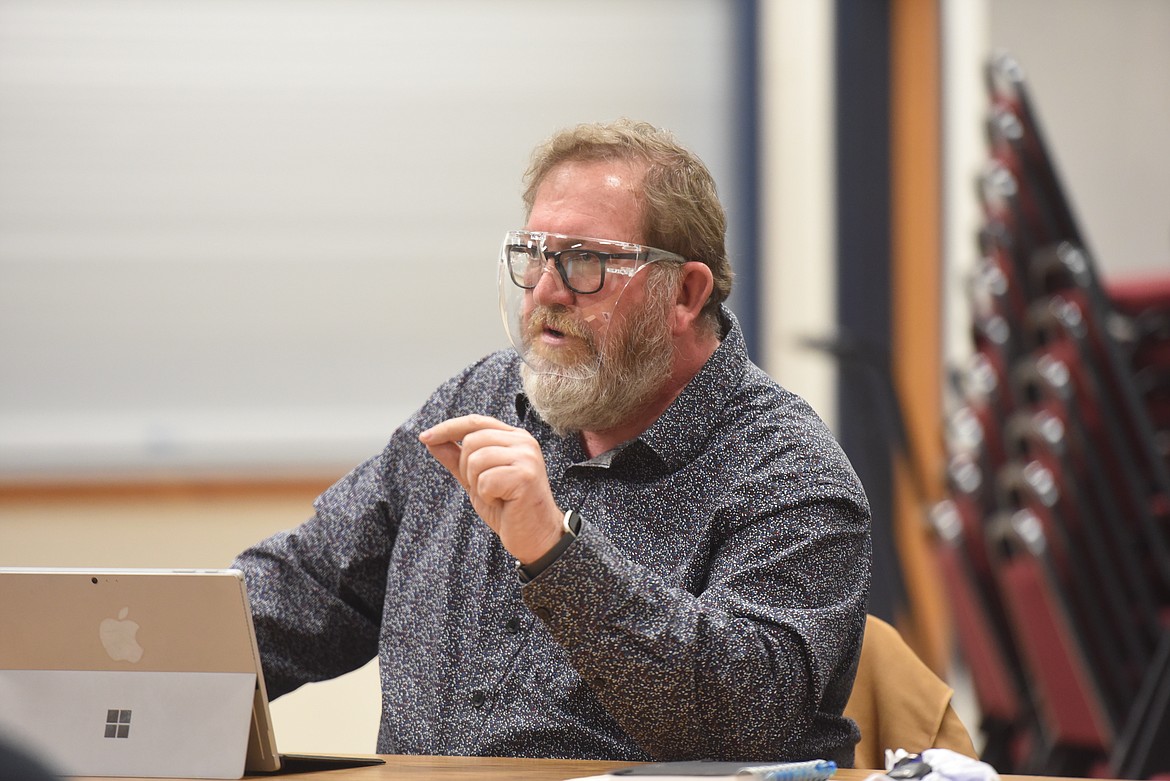

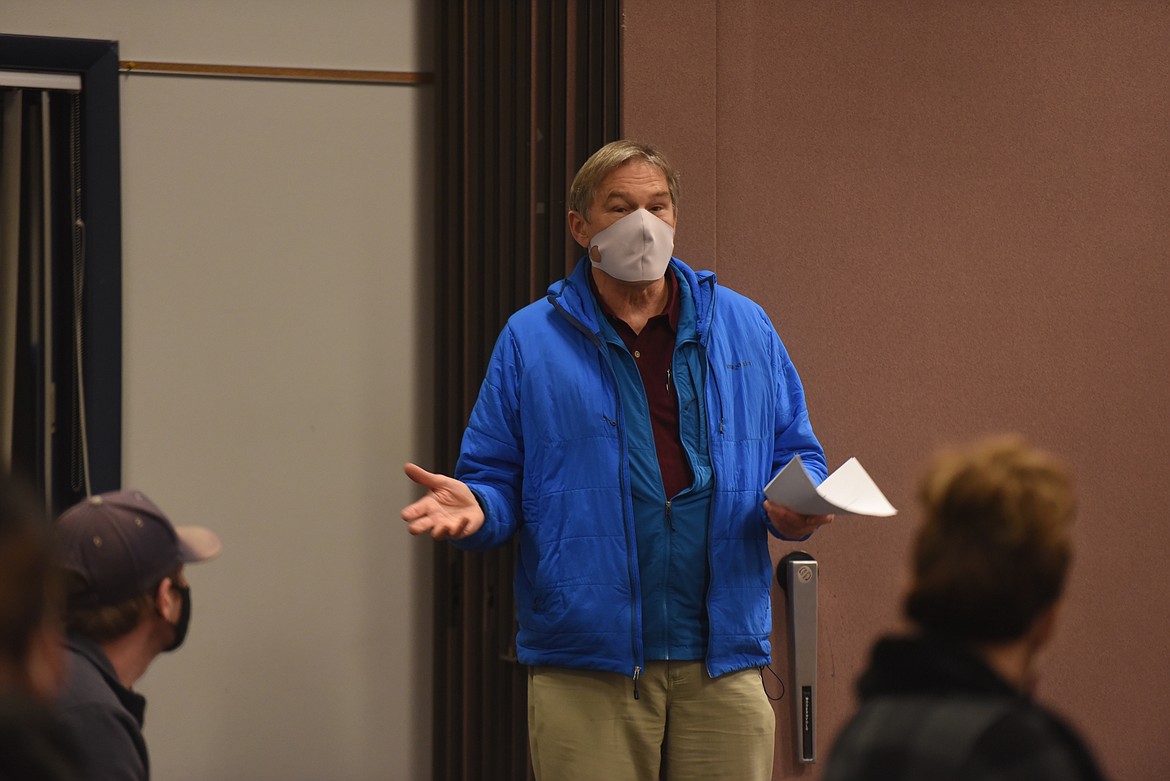

As coronavirus cases surged ever upward this month, members of the Lincoln County Health Board amplified calls for residents to join in common cause against the pandemic’s worsening spread.

The board did not add any additional restrictions to Health Officer Dr...

Become a Subscriber!

You have read all of your free articles this month. Select a plan below to start your subscription today.

Already a subscriber? Login