Despite long road ahead, Hecla officials remain committed to mining projects in Lincoln County

One question often posed by Lincoln County residents to Hecla Mining’s regional skeleton crew is, “When will you start hiring?”

It’s a question without a definitive answer.

First, federal and state agencies, judges and regulators would need to allow Hecla to move forward with the evaluation phase for the Montanore project, south of Libby, or the Rock Creek project, closer to Noxon, or both.

The evaluation process alone could require three to five years at each site. If Hecla’s assessment of the two proposed underground mines’ geology, hydrology, environmental impacts and economic feasibility convinces the company that mining could proceed, Hecla would then need to shoulder anew a lengthy environmental analysis process and acquire all the necessary permits.

Idaho-based Hecla also would have to sell agencies and regulators on impoundments for tailings from the mines’ milling of copper and silver ore.

History suggests many environmental groups would be staunchly opposed and poised for litigation.

Which begs another question. Will actual mining ever occur at Montanore or Rock Creek?

Luke Russell, a spokesman for Hecla, said he believes mining will proceed.

He said the Montanore and Rock Creek projects would mine two of the largest undeveloped silver and copper deposits in the United States. He said demand for copper and silver will increase as the nation moves toward renewable energy alternatives such as solar panels and wind turbines and embraces hybrid and electric vehicles.

Russell said mining these metals domestically rather than relying on imports ensures that the U.S. is not supporting countries with lackluster environmental standards.

“With all of that, we’re very optimistic these projects will be developed,” he said.

Nick Raines, a Libby-based employee of Hecla Montana, a subsidiary of Hecla Mining, received a warm reception Feb. 5 when he updated Lincoln County Board of Commissioners about the Montanore and Rock Creek projects and the Troy Mine, now in reclamation.

Raines, accompanied by consultant Bruce Vincent of Environomics of Libby, briefly referenced some of the litigation and rulings that have so far helped stymie development of the Montanore and Rock Creek mines.

Board Chair Mark Peck told Raines the commissioners will do what it can to help. The Montanore Mine would be in Lincoln County and the Rock Creek mine in Sanders County. The ore bodies they seek to mine are primarily in Sanders County.

“If at anytime you feel you are being stonewalled, we’ll be more than happy to jump in and raise hell,” Peck said.

Later, he acknowledged that the commission’s support for the projects, especially for the Montanore Mine, stems from potential employment, tax revenues and the stimulation of related economic activity. Lincoln County could benefit from property taxes on the Montanore Mine’s infrastructure, Hecla’s purchases of goods and services and more.

Bennett said the commission is in full support of the Rock Creek and Montanore projects because both mines would be good for Lincoln and Sanders counties.

Lincoln County’s unemployment rate for December was 8.5 percent, compared to the state’s jobless rate of 3.4 percent.

Hecla said it anticipates spending $30 to $40 million on the evaluation phase at the Rock Creek and Montanore mines. The company said related tasks will require between 30 and 35 full-time workers.

“Given the limited duration of this work, it is anticipated that most [of these workers] will be contractors,” Hecla officials said.

If the projects someday lead to mining and milling ore, employment would likely range from 300 to 450 full-time workers per site, company officials said.

Hecla officials said mining operations at the Montanore site are expected to last 16 to 20 years. Hecla projects a longer life expectancy for the Rock Creek mine.

Current Lincoln County Commissioners Peck and Jerry Bennett, along with former colleague Mike Cole, published an op-ed in April 2018 that expressed support for Hecla Mining.

“The Hecla purchase of the Troy, Rock Creek and Montanore mines is the single most positive event in south Lincoln County since the Neils family established J. Neils Lumber Company in the early 1900s,” the commissioners wrote. “Hecla has become significant community partners without turning a shovel.”

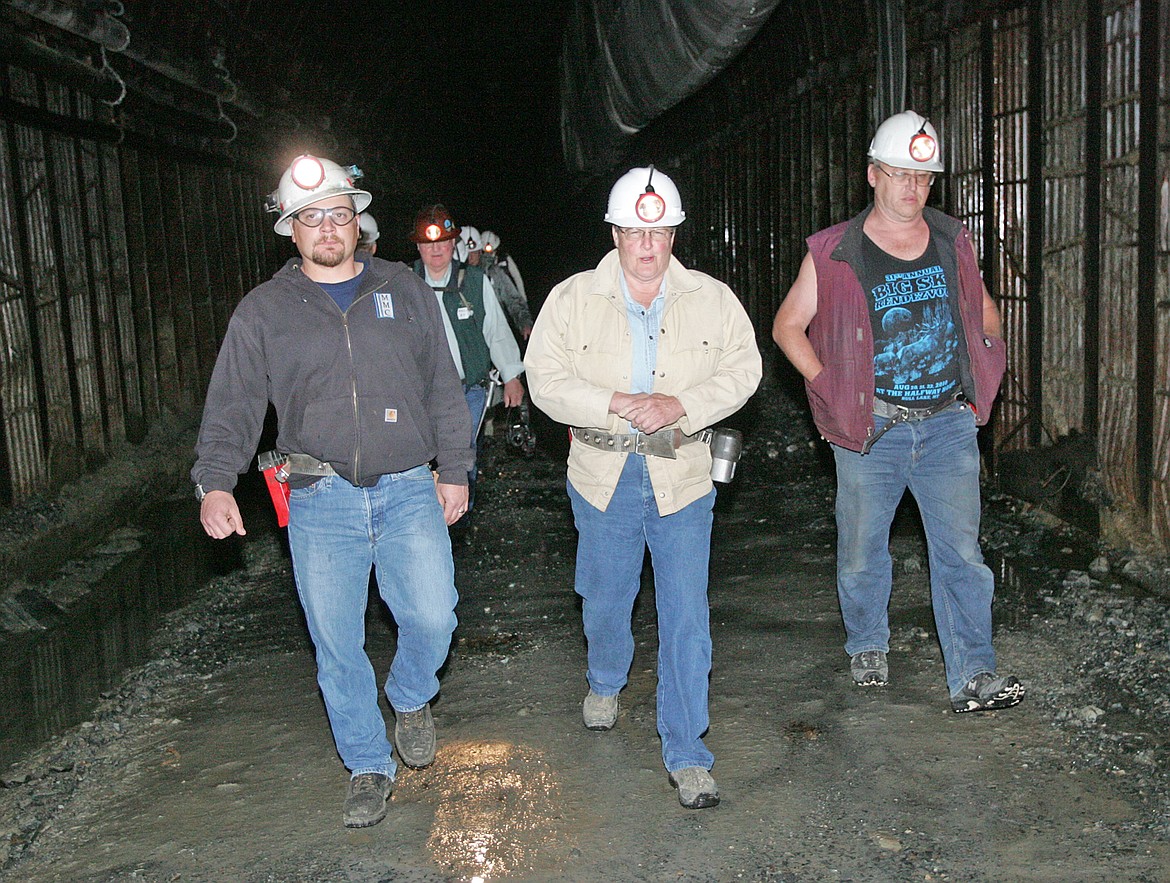

Both the Rock Creek and Montanore mines would tunnel beneath the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness. A previous owner drilled an adit for the Montanore project. If evaluation moves forward, Hecla would need to drill roughly 4,000 feet more to extend the existing adit, a roughly horizontal passageway of about 14,000 feet, above the ore body.

Evaluation at Rock Creek would require construction of a 6,300-foot adit.

During a Feb. 17 interview, Raines and Vincent said a key focus of the evaluation would be hydrology.

Opponents to both projects contend that mining and related groundwater pumping will dewater wilderness streams, robbing water from bull trout and other native fish that depend on the cold, clean streams of the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness.

The U.S. Forest Service’s description of the 94,272-acre Cabinet Mountains Wilderness touts its scenery and water quality: “Clean and pure are the simplest and most accurate ways to describe the water that comes out of the wilderness. Past studies have rated this water among the top 5 percent purest water in the Lower 48 states.”

Concerns about the mines’ potential impacts on water quantity and quality are among the key issues raised by opponents. Litigation initiated by environmental groups has targeted state water permits, federal environmental impact statements and biological assessments.

For example, in May 2017 a federal judge directed the Forest Service to conduct additional environmental analysis of the proposed Montanore project. In June, the Kootenai National Forest released a draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement for the Montanore Evaluation Project.

Willie Sykes, a spokesman for Kootenai National Forest, said Feb. 6 that the agency is “working on response to comments to formulate the new Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement.” In addition, he said, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is reviewing the Forest Service’s biological assessments for the Montanore project. The assessments were submitted Dec. 20.

Raines told commissioners he believes the Forest Service will publish the supplemental environmental impact document in late 2020.

Both the proposed Montanore and Rock Creek mines hit snags related to previously issued permits tied to water quality or water use because of separate court decisions in 2019.

Regarding Montanore, a state district court judge vacated the renewal by the Montana Department of Environmental Quality of a water discharge permit. DEQ has appealed the July ruling by Judge Kathy Seeley of Helena to the Montana Supreme Court and that case is pending. The site’s previous permit remains in effect for Montanore’s discharge of water from the existing adit.

Earlier, in April, Seeley had reversed a decision by the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation to grant a water use permit for the Rock Creek project. Seeley’s ruling found that the DNRC violated state law by ignoring evidence that groundwater pumping for the Rock Creek mine would degrade streams classified by the state as “outstanding water resources.”

The DNRC appealed Seeley’s decision. That case too is pending before the Montana Supreme Court.

Environmental groups contend both mines or their tailings impoundments would contaminate and reduce flows in pristine streams, creating additional hazards for bull trout, a threatened species, and causing other long-lasting environmental damage.

Hecla officials said buffer zones would help protect surface waters above underground mining operations and that there would be “little to no effect on stream flow or lake depth throughout the life of the mine.” The company said hydrological models project a reduction of 4 percent or less in the base flow at the mouths of Rock Creek, Bull River and East Fork Bull River “at the end of the mine’s life.”

Jim Jensen, executive director of the Montana Environmental Information Center, said the nonprofit’s decades-long opposition to the Rock Creek and Montanore mines reflects strong concerns about the projects’ potential to bleed water from pristine streams and effect bull trout, grizzlies and lynx.

Andrew Gorder, legal director for the Clark Fork Coalition, described similar concerns. He said the coalition’s opposition will continue until Hecla can demonstrate that the projects will not unlawfully dewater streams and lakes classified as outstanding water resources.

Jensen said there also is always potential for pollution from acid-mine drainage.

Society must decide, he said, whether the preservation of wilderness and remarkably pure water offers a higher value use of public lands than mining minerals.

Hecla officials have said the rock the mines will encounter has a low potential for acid-mine drainage.

“They always say this,” Jensen said. “Mother Nature bats last.”

Meanwhile, Montana’s “bad actor” mining law has been another big foot on the brake for Hecla’s plans at Rock Creek and Montanore.

In March 2018, the Montana Department of Environmental Quality alerted Hecla that it is in violation of the state’s “bad actor” law because the Idaho company’s president and CEO, Phillips Baker, was once a key executive for mega-polluter Pegasus Gold Corp.

Pegasus operated cyanide heap-leach gold mines in Montana that included the Beal Mountain Mine near Anaconda, the Basin Creek Mine near Basin and the Zortman-Landusky Mine near the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation.

Pegasus filed for bankruptcy in 1998. Taxpayers have been saddled with cleanup costs of pollution from the mines.

The “bad actor” provision in the Metal Mine Reclamation Act prevents former mining companies and executives from pursuing new projects in Montana if they have outstanding cleanup obligations to the state.

A March 20, 2018, letter from then-DEQ Director Tom Livers to Baker reported that “DEQ has spent millions of public funds on reclamation work” at the Zortman-Landusky, Basin Creek and Beal Mountain mine sites. Livers noted that ongoing reclamation at these sites would cost the state about $2 million a year in perpetuity.

Regional officials, including Peck, Bennett and State Rep. Steve Gunderson, R-Libby, protested the “bad actor” enforcement. As has Hecla. As has Baker. Litigation continues.

Gunderson, in a March 31, 2018, letter to Gov. Steve Bullock, described Hecla Mining as “one of the ‘best actors’ in the industry” and “an award-winning environmental steward.”

Raines said the “bad actor” designation for Baker has not seemed to affect the process of moving toward launching the evaluation phase at Montanore and Rock Creek.

Pegasus Gold aside, Hecla also has a history of pollution.

In June 2015, Hecla reached a settlement with the EPA and U.S. Department of Justice tied to the company’s water pollution violations near the headwaters of the South Fork Coeur d’Alene River in Idaho. Hecla agreed to pay a penalty of $600,000 for violations that occurred between 2009 and 2014 at its Lucky Friday Mine and Mill near Mullan.

At the time, the EPA said the South Fork of the Coeur d’Alene River was “already compromised due to dissolved metals from historic mining activities.”

The agency said the Lucky Friday mine operations “are seen as the highest single contributor of metals to the South Fork above Mullan.”

According to Hecla, the Lucky Friday is a deep underground silver, lead and zinc mine.

Hecla, which traces its roots to 1891, also agreed in 2011 to pay $263.4 million, plus interest, to the United States, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe and the state of Idaho to resolve the company’s financial liability for historical releases of heavy metals into the environment. The settlement stemmed from releases of lead, cadmium, arsenic and other contaminants in what became the Bunker Hill Mining and Metallurgical Complex Superfund Site in northern Idaho.

On the other hand, the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality recognized Hecla in September as a “2019 Pollution Prevention Champion.” The department lauded Hecla for a series of measures adopted at the Lucky Friday mine to reduce pollution, embrace renewable energy and recycle oil, lead batteries, antifreeze and scrap iron and steel.