Remembering a wild career

Troy writer, photographer earns lifetime achievement award for outdoor writing and photography

When Glenn Titus was a young photographer filming the first-ever documentation of the black-footed ferrets of South Dakota, he probably didn’t imagine his career would take him around the world and eventually earn him a lifetime achievement award in outdoor writing.

On Aug. 10, the Outdoor Writers Association of America announced Titus, of Troy, as the winner of the 2016 Excellence in Craft Award, a note of lifetime achievement for his work in outdoor conservation films, writing and editing.

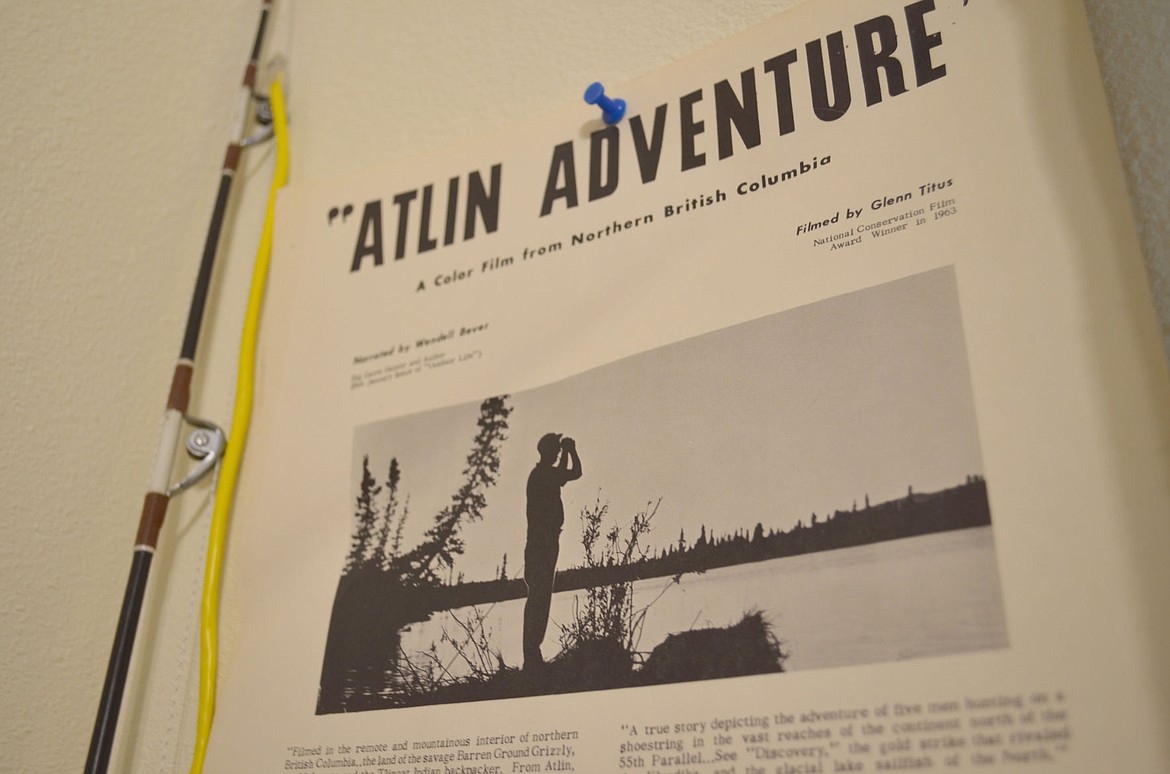

Titus began his craft with photography, eventually finding his way into some of the very first wildlife motion pictures featuring the American Midwest in North Dakota. He later became the outdoors editor for the Oklahoman, Oklahoma’s largest daily newspaper located in Oklahoma City. He filmed several outdoor pieces for different companies and state offices, from the Midwest and Canada, documenting the wildlife and people that shared his fascination along the way.

Today, the 86-year-old lives with his wife, Oleta, on a property outside of Troy on the Kootenai River. His home office features a wall of outdoors novels and guides, along with a few more awards and small wooden sculptures (the results of whittling while sitting in a tree stand during bow hunting season). A large log coin sits on a stand in his yard, where Titus and others occasionally aim a few hatchet tosses, although Titus said his stamina is not what it once was.

The Excellence in Craft Award, he said, is a nod to his career in all the mediums he would learn to master over his 60-year career in outdoors writing and photography.

“Where most of the recipients have been photographers or writers or TV personalities, I’ve been all of it,” Titus said.

Titus grew up in a small rural community in Pennsylvania on a farm in the 1930s. His family raised pigs and chickens and farmed what they could in order to put food on the table. Part of feeding the family meant hunting and fishing, which was what Titus said was the foundation for his love of the outdoors.

Titus began his photography work during his short stint in the military. After his discharge, he moved to Fort Collins, Colo., enrolled at Colorado State University and soon obtained a degree in wildlife management.

After college, Titus attended a National Wildlife Federation conference in Colorado, where naturalist and entomologist Ira Gabrielson pitched an idea for a wildlife management project that would enhance public knowledge and awareness of the concept.

“I picked that up as my life’s mission, being both a photographer and a biologist,” Titus said in August. “I put the two together.”

Titus moved with the project to South Dakota, where the crew started shooting a program on 16-millimeter film in Rapid City, called “Black Hills Outdoors.” It was there where Titus first gained recognition for his work in documenting the black-footed ferret.

“Interesting things happened during the filming of those shows, it was live,” Titus said. “This was before tape machines got out into the hinterlands, anyhow. We had a bobcat one night, the bobcat got loose and treed the camera man on top of his camera.”

Titus greatly enjoyed the work he’d found himself doing and the crew that he joined, so soon they began shooting films for hunters’ safety and boat regulations. After a few years, Titus moved to Oklahoma to become the chief of the information and education for the state wildlife department in 1964. The job included some public relations work, along with motion pictures and television programs funded by the state.

“Oklahoma was just coming out of the dust bowl days. We were showing all the practices on the land that would improve wildlife, like planting tree belts and that sort of thing,” Titus said. “Just telling stories in the films.”

During his time with the state in the 1960s and ‘70s, Titus went to the managing editor of the Oklahoman to raise some questions over their wildlife coverage in recent years. Titus believed he had come across corruption in the wildlife state office, where a state senator was using wildlife department land for personal projects and residential development, while incoming funds for wildlife licenses were being redirected out of the state budget.

“So I was harassing the managing editor about the lousy outdoor coverage, and he said ‘If you don’t like what we’re doing why don’t you come do it for us?’” Titus recalled.

Titus stayed with the Oklahoman for 15 years, covering the state’s policies and actions surrounding wildlife management in the state and illuminating backdoor deals that had become business-as-usual for many wildlife policies.

At one point in his news career, while speaking with a county commissioner and a state legislator in the halls of the county building, Titus said a man, the Chairman of the House and also the Fish Committee, walked up and punched him in the face, supposedly upset with Titus for asking too many questions. Titus was on the front cover of the newspaper the next day with a broken jaw.

“It was pretty rough and tumble back then,” Titus said. “It continued with the help of some of the guys from the wildlife department feeding me information and we got her slowed up anyhow. That went a long way toward straightening out the department and cutting down some of the corruption. Of course with all this, the public became more interested and it wasn’t so easy to steal from the wildlife department.”

After his tenure with the newspaper, Titus became a freelance writer and photographer, joining crews for outdoor films around North and South America. He relocated his base back to Fort Collins, but found that in 30 years the town had grown substantially in population and the environmental movement had taken hold of the wildlife conservation community.

Titus and his wife moved to Saratoga, Wyo., where he enjoyed the more remote outdoor lifestyle that had been lost in Colorado. He said in Saratoga, he could kill elk, moose, antelope, mule deer and whitetail deer all within five miles of his house near the North Blue River.

But eventually Oleta developed a lung issue and couldn’t breathe properly in the 7,000-foot elevation. So, he and Oleta moved to the lowest elevation community in Montana, Troy, and have resided on their property along the Kootenai River ever since.

“Troy is so much like the little town I was raised in, and the people are so wonderful,” Titus said. “I feel right at home, just like I’ve lived here all my life.”

Reporter Seaborn Larson may be reached at 758-4441 or by email at slarson@dailyinterlake.com.