Invasive fish spread across NW Montana

Kevin Alyea, a Troy native, remembers when he could fish on Kilbrennan Lake and catch fish after fish right from the edge of the shore. He said at that time, before the 1980’s, you’d have to throw back fish because there were so many.

He said with fewer fish and more lake weeds, you can’t fish on the edge of the lake anymore, and the entire environment has changed.

What may look like a lost fishing opportunity in the Kilbrennan is in fact a much more serious issue involving the entire northwest Montana water body system.

The effects of illegal non-native fish introduction into these waters, the lynchpin of the issue, have frustrated Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (FWP) agents and anglers alike and has sparked an effort to end the introductions that wreak havoc to the natural Montana waters through predation, overpopulation, species hybridization, competition, disease transmission and more.

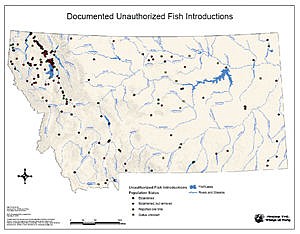

The key species that have been transplanted into northwest Montana waters are the northern pike, yellow perch, pumpkinseed, largemouth bass, black bullhead, smallmouth bass, white sucker, walleye, fathead minnow and bluegill, according to FWP documents — and the whole northwest Montana region is being affected by these species.

Loon Lake outside Kalispell has northern pike, yellow perch and whitefish. Bull Lake is overrun with pike and small-mouth bass. The Clark Fork has walleye. Island Lake down Pleasant Valley Fisher Road has large-mouth bass. Kilbrennan Lake has been hit by perch and bullhead populations. Eighty percent of Lake Mary Ronan gillnet catch are perch.

Mark Deleray, FWP fisheries manager, said illegal introductions go back to the 1970’s. Now, FWP region one containing Troy and Libby has had a total 283 illegal introductions, but no one in the Kootenai has been caught.

“It’s hard to find a lake now, of any size, that pike haven’t been introduced into,” Hensler said.

But why introduce a species into a place it does not belong? Hensler said fishers likely want to fish for certain fish like the pike, and thus, they will plant the fish into waters where they may not naturally come from.

For others, it’s not necessarily about the fish. Over thirty years later, Alyea said fishing in the area has drastically changed, for the worse — and it was out of his control. Whether it’s trout or pike, Alyea said the FWP should leave the discretion solely to residents.

“Let the people here control what we do with the fish and the waters,” Alyea said. “It’s ours, not anyone else’s.”

Steve Kalb, who owns Shoo Fly Fishing Co. in Troy, is a trout fisherman, and he doesn’t fish for pike. He said he thinks it would be good for the pike to be eliminated from the waters. The pike, a predatory fish, threatens any species in the water body it dwells, including trout. The more pike, the less trout, and the less trout fishers like Kalb will be able to fish.

“It’ll be soon where trout will be in danger,” Kalb. “And that’s something I have to think about.”

A watery conundrum

Whatever the reason for the introduction and the fishing of these species, the big problem to FWP is the fact that once they’re in a body of water, they won’t get out, Hensler said.

“Once the fish are in, they’re in,” Hensler said. “For good. They’re virtually impossible to eradicate.”

Once the pike take over, the native species have no way to compete, and by bad luck and the elusive problem of illegal introduction, these species may diminish. Hensler said each nonnative fish poses its own problems: with pike, for example, it’s an issue of predation whereas with perch, it’s a matter of overpopulation.

“We don’t have the space or the funding to replenish the (native) species,” Hensler said. “The question will become, especially in Bull Lake, ‘How can we stock the fish to overcome the pike?’”

One successful method in managing the rapid growth of introduced fish in regional waters is “rehab,” as Hensler said, where the chemical rotenone is used to “poison” the lake where non-native populations have gone out of control. This chemical rotenone kills all gill-breathing fish in the waters, but it is released in a low concentration so as not to kill other organisms in the lake.

After the chemical degrades, FWP re-populates the lake with native species, generally 100 fish per surface acre, said FWP fisheries biologist Matt Boyer. The fish killed from the chemical either degrade after sinking or are collected by FWP.

There are other ways FWP is approaching the illegal introduction crisis, Hensler said, although poison is the primary method in region one. They have used electrofishing, where an electric current is shot through a lake, stunning the fish so they can collect the introduced species. They also use gillnetting and trap netting.

This year, FWP established a rule that they have 30 days to respond to reports of an illegal introduction, a new stricter and quicker timeline for the agency. Hensler said new rule was done in an effort to speed up the process to find out the culprit.

A hard-to-catch crime

Although FWP has its own methods to try to solve the illegal introduction problem, the anglers and fishers themselves take a major role in how the issue plays out.

It’s up to local agents, like game warden Phil Kilbreath, to enforce laws set to crack down on the rapidly growing nonnative fish populations. With two separate boats for rivers and lakes, Kilbreath conducts both safety and fishing checks to make sure fishers are in tune with lawful fishing.

Kilbreath clarifies that catching the fish is not illegal; physically implanting the fish in the water is what’s illegal.

“It’s fine that people want to catch them,” Kilbreath said. “We just don’t want people to take them and move them to another spot. It’s a big jump from ‘I like catching fish’ to ‘I like catching fish and I’m going to take this one and put it in another lake.’ That’s the difference.”

Kilbreath said the violations can range from a $735 fine to loss of a fishing permit, Beyond this, an offender could be subject to pay for the cost of getting the fish out of the water, which can lead to thousands of dollars in fines. But if someone is found illegally introducing a species into public waters — the worst crime— it is a felony, with no bond.

Once away from the watery edge, every vehicle toting a boat must also stop at inspection stations after fishing in the region’s waters. Fish must be dead once a vehicle hits the road, and if someone is caught with a live fish, the fines can range between $135 and $700.

At the Troy inspection station, located at the junction of Highway 2 and Bull Lake Road, inspection agents post out every day next to the rest stop to check boats for standing water, microorganisms and to make sure no one is illegally transporting species.

Kilbreath and Charlene Craft, who works at the Troy inspection station, said the area has not this year had any illegal introduction violations. Hensler said the Kootenai area of region one hasn’t yet caught anyone introducing species.

How effective have the measures been?

“For us, it’s about framing the argument in a way that doesn’t look adversarial,” Hensler said.

He said it’s understandable how the FWP efforts can appear aggressive.

Communication about the issues of illegal introduction is difficult, Deleray said. He said the agency has sent out media releases but the effectiveness is hard to gauge because the introductions keep happening, and considering the last few decades of illegal introductions, the problem has worsened.

A statewide reward system has started in certain fisheries to combine the likes of fishers and the enforcement efforts —anyone with a tip can call in to 1-800-TIP-MONT. Deleray said organizations have gotten together to offer rewards for tips on arrests of fishers who may be introducing species.

Deleray said the agency holds nothing against innocent fishers.

“There’s nothing wrong with pike,” Deleray said. “All of these fish are great, and fishers love them. I understand why. But the problem is that they just can’t be everywhere.”

Dave Blackburn, owner of Dave Blackburn’s Kootenai Angler, is a trout fisherman, and he guides trips down the Kootenai River. Although he said the river is less likely to be overrun by nonnative species, he said that it’s concerning to see the pike cropping up in places where it isn’t native.

He said that the anglers he encounters are experienced and know what they see when they catch a fish, and in Montana, it shouldn’t be a pike.

“Those fish are out of place here, that’s for sure,” Blackburn said. “People come here from all around the country, and they aren’t — or shouldn’t be — fishing for pike. That’s just not what Montana waters are for. It’s easy to see that.”