Wilderness designation sought for Scotchman Peaks

HERON — In the often-divisive arena of wilderness policy, the Scotchman Peaks straddle many boundaries.

The scenic mountain range between the Clark Fork and Bull rivers has more geopolitical lines dotting its map than a United Nations seating chart. About 20,000 of Scotchman’s 88,000 roadless acres lie in the Panhandle National Forest on the Idaho side of the border. The Kootenai National Forest in Montana has the rest. Three counties in two states have jurisdiction of the area.

The Friends of Scotchman Peaks hope to change that. In the process, they hope to reframe the wilderness debate in the United States.

“We’re wondering - can we do this? - can we identify a place as an inspiring, appealing candidate for wilderness and make it go?” asked Doug Ferrell, a Trout Creek construction designer and founding member of Friends of Scotchman Peaks. “A lot of the wilderness community is wondering if we can pass a true wilderness bill anymore. Scotchman is a great candidate. It’s rugged, well-supported and needs protection.”

The 135-square-mile area has a major copper/silver mine on its eastern border, whose owners publicly support its wilderness qualities. All three county commissions have backed it, and members of Idaho’s Republican congressional delegation and Montana’s Democratic senators have backed it. Nevertheless, it hasn’t yet made it into any draft legislation.

“What’s enlightening is how much we have in common,” said Philip Hough, a Friends of Scotchman member from Sandpoint, Idaho. “We live here for the same reasons they live here. We don’t want the timber industry to go away.”

Latent political inertia still makes it productive to frame arguments as “wilderness vs. timber,” Hough said. But a bigger divide may lie within the old “wilderness” community, as it tries to accommodate mountain bikers who want to ride into roadless areas and old-school activists who won’t support new protections that include concessions to industry.

Ferrell also sits on the board of the Montana Wilderness Association. The organization has drawn criticism from former allies who accuse it of selling out the movement by pushing for Montana Democratic Sen. Jon Tester’s Forest Jobs and Recreation Act - a bill that designates 660,000 acres of new wilderness (not including the Scotchmans), but also mandates annual logging and thinning work on national forests.

Some of those opponents, such as the Alliance for the Wild Rockies, regularly challenge the Forest Service in court over presumed failures to protect threatened animals and landscapes.

“I think all the litigation is killing the positive image of conservation in the public mind,” Ferrell said. “Around 10 years ago, some people started thinking there had to be a better way. Wildland protection wasn’t a threat to getting the cut out.”

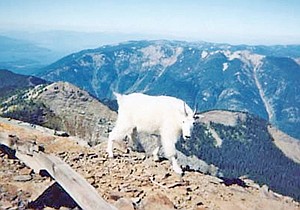

The Scotchman Peaks have many of the qualities that make wilderness a hard sell. You can’t see them from the ground - there’s no highway turnout where snow-capped peaks or sparkling waterfalls can wow tourists. Almost every trail into the area involves thousands of vertical feet uphill before any postcard vista appears.

Scotchman is also too rocky, too wet and too worthless to develop. While it has valuable timber, the trees grow out of steep cliff shelves that make road building almost impossible. A turn-of-the-century railroad considered building a spur line into the mountains, but determined it was too hydrologically unstable - no safe place to lay tracks. A proposed helicopter logging project in the 1970s never penciled out.

The Pacific Maritime rainforest nearly ends at the Scotchmans. The Great Burn of 1910 charred most of western Montana’s cedar-hemlock groves. But like the Avalanche Lake Valley in Glacier National Park and Cedar Creek near St. Regis, pockets of massive cedar forests lurk in the Scotchmans’ deep defiles.

Lightning Creek, on the Idaho side of the Scotchmans, ranks as the wettest place in that state. It recorded 10 inches in one day in 2006, which is almost the annual average for the entire state of Montana. Its annual tally approaches 90 inches. Hough said biologists believe between 5,000 and 6,000 species of lichen grow in the soggy bottoms, of which less than 1,600 are known to science.

The 147-square-mile Cabinet Wilderness just east of the Bull River won its designation in the original 1964 Wilderness Act passage. But the Scotchmans missed out, although they have equally valuable qualities. The range was recommended for wilderness designation in 1987, but President Ronald Reagan vetoed the bill that would have made it official.

With all those obstacles, one might ask: Why bother with a “Big W” wilderness designation? The place seems to protect itself.

Ferrell offered two reasons. First, the Scotchmans aren’t as tough as they look. Its thin soils probably wouldn’t withstand much mountain biking, and snowmobiling poses risks to the mountains’ tottering populations of fisher, wolverine and grizzly bear.

“And second, it’s a good thing to show a little restraint,” he said. Putting a wilderness designation on the place declares it has a value in being left alone. Even though they’re as hard to play in as profit from, the Scotchmans deserve respect.

As a boy, Ferrell often traveled from Wisconsin to fly-fish with his grandfather in Montana. He moved to Trout Creek, just east of the Scotchmans, in 1974. He worked for a Louisiana Pacific Corp. timber mill in Trout Creek for three years before moving to construction.

That was about the same time what the Pacific Northwest came to know as the Timber Wars was heating up. The 1980s saw political careers made and friendships dashed as the fate of Montana’s forests became a policy football.

Shortly after he moved to the state, he attended a slideshow about the high country of the Cabinet Mountains.

“It was on this creaky old slide projector, but it really grabbed me,” he said. “I wanted to go there, and I did. Then I got wrapped up in its protection.”

Philip Hough came to respect the Scotchmans through a family history of prowling wild places. His great-grandfather, Franklin B. Hough, was the first chief forester in the U.S. Department of Forestry in the 1870s, before President Theodore Roosevelt created the Forest Service.

His grandfather Philip Rice Hough was the first ranger in Great Smoky Mountains National Park and later helped complete the first survey of Alaska’s Brooks Range northern boundary in 1921.

“My grandfather was 60 when my dad was born,” Hough said. “Dad was interested in hiking, but they didn’t get to do much together. So he passed the interest on to me.”

A very young Hough ran out of money on one hike into Lake Chelan’s remote Stehekin Village. He offered to wash dishes at the resort, and soon talked his way into cooking breakfast and lunch in the dining room. That launched a career in the hotel industry that took him around much of the country.

But as he grew older, Hough said he realized he preferred hiking to working. So he switched to the catering side of the business, where he could work on specific projects and have time for the woods. And he bagged the hiker’s triple crown: the Pacific Coast Trail, Appalachian Trail and Continental Divide Trail.

“Yet in all those wanderings, this is as wild a country as anywhere I’ve stepped foot in the lower 48,” Hough said. “For me, that just drives me to see that opportunity is available for the future.”