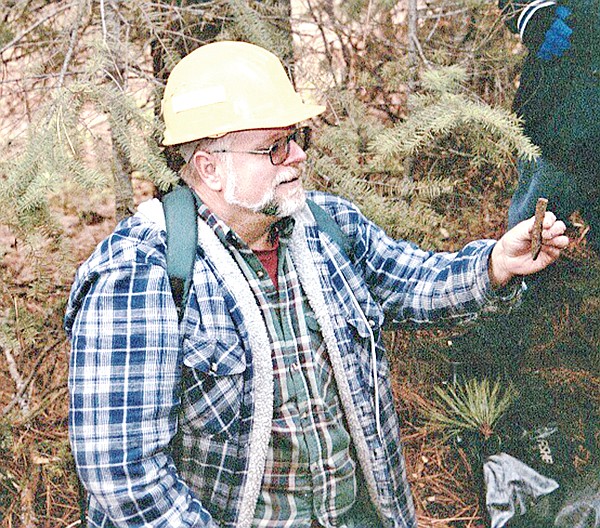

Historian to remember: Mark White

Where the casual observer only notices trees, U.S. Forest Service archeologist and historian Mark White saw remains of settlements and a glimpse into life of northwest Montana’s pioneers.

“To Mark’s eye, he could still find ditches, he could find foundations, he could find rotten roof logs and old railroad grids and make sense of what happened over a hundred years ago,” recalled White’s friend and fellow historian, Jeff Gruber.

The man who contributed significantly to today’s historical knowledge of northwest Montana died of pancreatic cancer early last week at the age of 54. Though White was diagnosed last spring, he continued working as a detective, investigating and rooting out little known details to solve mysteries of the past, clear until the end.

The northwest region of the state has been but a footnote in Montana’s history books, according to Rich Aarstad, archivist and historian at the Montana Historical Society in Helena. White’s research has helped give a clearer narrative of the area’s past.

“Mark was one of the few individuals who really embraced northwest Montana history and local history,” Aarstad said. “I think that made him unique in that respect because, unfortunately, that part of Montana hasn’t seen that much play.”

White spoke in Helena at a Montana Historical Society conference in 2007 about his search for the site of one of explorer David Thompson’s first trading posts in the early 1800s along Kootenai River. He pieced together clues from several sources and finally, not too long afterward, solved the mystery. The site lay at the Canoe Gulch Ranger Station.

“I vividly recall him calling me and telling me that he found it,” Aarstad said. “He said, ‘It’s exactly where I always thought it was at.’”

While researching historical archives in Helena, Gruber had come across a photograph from the 1940s or 1950s that went on to help White complete the puzzle. The photo was only of a man standing outside, but its label read, “near the ruins of old Fort Kootenai.”

“You really couldn’t see anything – it was just a field – but I got a copy of it and gave it to Mark. He said, ‘Oh my gosh, I can find it now,’” Gruber recalled. “He goes to where that photograph was taken, uses ground-penetrating radar and found it.”

In that era structures didn’t have foundations, Aarstad said, making ruins more difficult to uncover.

“It was a pretty amazing work on Mark’s part,” he said. “He was good at looking at obscure sources and finding details that helped pinpoint that location.”

Heavily involved in the Libby Pioneer Society and the Heritage Museum, White shared the area’s history through lectures, presentations and field trips into the woods. He had the natural ability to piece together different events, people, places and dates into stories that listeners could relate to.

“It wasn’t just an encyclopedic review of a date or a happening or a person or a place,” Gruber said. “There was meaning to it and a love the people just enjoyed hearing about. He enlivened history.”

White spent hundreds of hours at the Lincoln County Library looking through old newspapers on microfilm and hundreds more sifting through archived work in Helena, but he also learned and researched by talking to longtime residents and discovering what documents and artifacts they had stored away.

“He helped preserve all these records that we wouldn’t have had if he hadn’t dug them out of people’s attic or basement,” Aarstad said. “He gathered these records with the purpose of saving them, so the history itself would be saved and preserved.”

When Aarstad was writing his master’s thesis on a 1917 timber strike in Eureka, the ever-resourceful White located the company’s records – documents that Aarstad went on to base a major part of his thesis on.

“He knew where all the good stuff was,” Aarstad recalled.

White made sure the company records were stored safely in Eureka and convinced the owners to make copies to archive in Helena.

When he died, White left behind his wife, Tami White, and four children, as well as a project that Gruber believes had been tailor-made for him.

“Probably the task that was left undone was he was the one that should have written the concise, detailed history of Libby,” Gruber said. “I think he would’ve done it when he retired, and he was just the right person for it.”