The Montana Gap The lifelong consequences of childhood trauma

(Editor’s note: This story was produced by the Valley Journal as part of The Montana Gap project, in partnership with the Solutions Journalism Network and in which The Western News is participating.)

There’s a problem and we all have the solution.

According to The Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University, “When adults have opportunities to build the core skills that are needed to be productive participants in the workforce and to provide stable, responsive environments for the children in their care, our economy will be stronger, and the next generation of citizens, workers, and parents will thrive.”

Individuals, communities and the nation have within their grasp information that can improve childhood experiences, family relationships, community security, national student success rates and public health.

A study of adverse childhood experiences (ACES) occurred at a Kaiser Health Facility in Los Angeles in the mid 1990s. Health professionals found that early trauma, especially recurring trauma and toxic stress and extending activation of the stress response system, predicted chronic health problems in adults by compromising immune systems and speeding up disease processes and aging.

Dr. Robert Anda, an epidemiologist who worked on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ACE Study states, “… this information needs to go out to everyone,” and “What’s predictable is preventable.”

Adverse childhood trauma affects physical health, emotional balance, academic and professional capabilities and often interrupts lives with early death. Traumatic experiences include sexual abuse and or assault, parental loss, neglect, and serious illness.

Heart and lung disease, cancer and diabetes, along with many other health risks and adult diseases, are related to the number of ACEs experienced during childhood. As a child’s number of ACEs goes up so does the likelihood of experiencing serious health issues from childhood through adulthood.

Robert W. Block, MD, FAAP, past president of the American Academy of Pediatrics states, “Children’s exposure to Adverse Childhood Experiences is the greatest unaddressed public health threat of our time.”

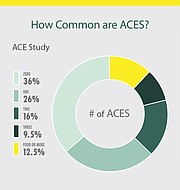

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network estimate two-thirds of Americans experience at least one traumatic event before age 18, and more than one in five reported an ACE score of three or more. Exposure to four or more adverse experiences in childhood increases the likelihood of alcoholism, drug abuse, depression and makes a person 12 times more likely to attempt suicide. Those with an ACE score of six or greater predictably die 20 years younger than the rest of the population.

According to the CDC, Montana’s rate of suicide is at 29.2 per 100,000 residents, compared with the national average of 13.4 per 100,000 residents. Survey statistics gathered from 2005-2014 point to Montana’s American Indian youth being an especially vulnerable segment of the population.

Life doesn’t happen without stress, and while some stress benefits children and prepares them for future challenges, trauma and chronic, unrelenting stress alters a child’s developing brain. During the first three years, the brain networks more than any other time in life. Repeatedly hearing alarming sounds, seeing visions of violence, and having feelings of instability, creates an amplified sense of alertness and toxic stress. Licensed Clinical Social Worker Stacy York, who works with traumatized children and recently spoke at Salish Kootenai College about parenting and childhood trauma, explains that some children exposed to toxic stress have elevated heart rates even when at rest.

The mind and the body work in symphony Andapting to stress with habits, impulses, and mental attitudes used to ensure survival, to feel better and to compensate for what is needed and not provided. Common “reactionary” coping skills include: yelling, crying, lashing out; shutting down; working to please everyone; blaming and manipulating others.

Trauma causes the brain’s alarm system in the amygdala to engage, triggering fighting, running or freezing responses. Children experience trauma differently than adults. Adults can regulate initial reactions to trauma using coping mechanisms and previous experience. These adult complex thinking processes haven’t developed in young children. Continual stress appears to cause more damage than a one-time event. Without the reassurance of a compassionate adult, stress and trauma lay unresolved and stores of stress-related hormones released by the brain’s activated amygdala stimulate diseases.

Children may not remember certain traumas but their bodies absorb the experiences causing mental and physical long-term harm to health. According to Jane Stevens, creator of the “ACES Too High” website, this scientific knowledge is “shifting (us) to another level of knowledge about our human development.”

Knowing and understanding ACEs empowers a person to heal. Awareness prompts the development and use of resiliency and other protective factors that defend against the symptoms of ACEs.

The neuroplasticity of our brains allows healing, rewiring and new coping skills to develop. Healing from trauma occurs with protective factors and resilient thinking. Resiliency is learned. We’re taught to bounce back from adversity, overcome challenges and remain hopeful by making connections with others, avoiding thinking of problems as impossible, accepting change, moving towards goals, taking action, self-discovery, nurturing a positive self-view, keeping perspective, having a hopeful outlook, using self-care like meditation, exercising, eating with good nutrition in mind, getting adequate sleep, and maintaining healthy social interactions.

Protective factors for children include having a resilient parent - someone who understands good parenting and child development, who nurtures and encourages attachment.

Like many states in the country, Montana, is using ACEs research to benefit children. Best Beginnings Children’s Partnership of the Flathead Reservation and Lake County, promotes and provides opportunities for affirming adult-child interactions. As a collaboration of organizations their chief goals include making children’s first crucial years beneficial to encourage positive life outcomes.

Similarly, SafeStart is a special Early Head Start program for children from families with low incomes and drug or alcohol addiction in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Rather than pointing out neglectful or abusive behaviors, the program benefits families by addressing family relationships, mental health issues and home economics. Approximately 84 percent of the children enrolled gained full resolution of their symptoms when they aged out of the program. Most children began with developmental delays, health and emotional difficulties. By investing in children’s well-being the risk of prenatal drug exposure and teen suicide lowers, while school success increases.

Creating healthy mental and physical beginnings for children diminishes the likelihood the effects of trauma repeat from one generation to the next. Epigenetics, the science of how social or environmental factors turn genes on or off, has shown that trauma can be passed on to the next generation. For example, you may have a predisposition for depression, or heart disease, but what turns on or off the genes for that disease may begin early in your childhood, even prenatally.

Suicide appears to offer relief to some with unresolved mental health issues. Montana’s serious suicide problem requires its citizens to unceasingly address this issue.

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that communities, (some are in Montana), using the Garret Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program, showed a significant decline in the number of suicide attempts in the first year following implementation for 10 to 24-year-olds. This was especially true in rural areas. The program trains gatekeepers, increases screening activities and improves communication between programs and services. A collaborative report entitled, “Pain in the Nation: The Drug, Alcohol, and Suicide Crisis and the Need for a National Resiliency Strategy,” reports that more than 79,000 suicide attempts were prevented by instituting this program. However, analysis showed no significant change in subsequent years. This was attributed to declining program use suggesting consistent effort could provide ongoing success.

As a successful approach to healing ACEs, trauma-informed care, takes into account the traumatic experiences of children and adults and treats them accordingly. Dr. L. Elizabeth Lincoln works as a primary care physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, a facility ranked as one of the top hospitals in the country by US News and World Report. She states that, “Trauma-informed care is defined as practices that promote a culture of safety, empowerment, and healing.”

“BARR method, for Building Assets, Reducing Risks,” incorporate trauma informed care into school curriculum. The method prioritizes positive teacher-student relationships and considers the source(s) of students’ problems and misbehavior rather than automatically suspending them. Schools using this method hold staff meetings to share student concerns and information, creating a more holistic picture of each student. Angela Jerabek, originator of BARR, claims students work harder when they believe adults care about them. Randomized and controlled trials of BARR show that in large-city schools there is a 40 percent decrease in school failure and in smaller rural schools there is a decrease of about 29 percent. Jerabek expects the program to grow from the current 80 schools to 240 schools in the next five years.

Schools, medical offices, even the workplace present opportunities to use a trauma informed approach to relationships and or treatment.

The good news that our brains and bodies work together to heal symptoms of stress begs the questions, “How do I make this happen,” and “What can I do to help myself and others heal?”

Begin with understanding your own ACEs. Discover your ACE score and find out how resilient you are. Take action … for yourself, your family and your community. The repercussions from ACEs enter classrooms, courtrooms, and makes news headlines. Everyone pays the price for adverse childhood experiences.

Parents who make social connections, find support for themselves and encourage their children’s social and emotional growth, provide a blanket of comfort and protection against stress and trauma.

Educate yourself about what adverse childhood trauma looks and feels like. Learn what as an individual you can do to help yourself and the children in your life. Grow in resiliency and wellness to counteract the symptoms and effects of childhood trauma and to protect upcoming generations. Bring healing, empowerment and safety to work with you. James Redford, producer of a documentary on resiliency said, there needs to be “an opening of the heart.”

Invest in community programs that promote healthy family relationships, encourage positive parenting techniques and provide early learning opportunities in places with well-educated and caring staff. Support programs such as CASA that provide advocates for children suffering from abuse and neglect.

Healthy, secure and happy childhood experiences created by adults capable of regulating their own emotions does more to ensure the longevity and success of future generations than all the pharmaceuticals and medicine available today.

The issue of ACEs belongs to everyone and within everyone lies the problem as well as the solution.

Kathi Beeks is a reporter with the Valley Journal.